Oct. 26, 1921

One-hundred years ago a native Morrow Countian stood before some 100,000 people in Birmingham, Alabama and delivered a powerful speech on civil rights that shocked the country.

Warren G. Harding, fresh from a landslide election, enjoyed considerable popularity following his effective campaign promising the country a “return to normal” following the Spanish Flu Pandemic and the First World War.

Harding chose to use that popularity to address race relations following the horrifying Tulsa, Oklahoma massacre that destroyed the successful black community of Greenwood. In context, Harding took office immediately following Woodrow Wilson who re-segregated much of the federal government, adamantly defended the Ku Klux Klan, and even screened Birth of a Nation at the White House.

Given how the presidencies of Lincoln, Garfield, and McKinley ended, Harding showed great courage for his trip to Alabama that was the first outing into the Deep South by an American President since the Civil War. It would be another 40 years before a president would again speak on the issue of race in the deep south.

Beginning his speech in Woodrow Wilson Park, Harding told the crowd he was going to speak frankly to them “whether you like it or not.”

Now, parts of his comments, viewed in today’s standards, are troubling to read. Hard and upsetting to read. Still, the totality of his comments were revolutionary for 1921, and the black audience listening in-person cheered his insistence on economic and political equality for blacks.

The president “declared that the Negro is entitled to full economic and political rights as an American citizen,” reported The New York Times. “In this the president made a braver, clearer utterance than Theodore Roosevelt ever dared to make or than William Taft or William McKinley ever dreamed of,” wrote civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois.

A few standout comments from his talk include:

“I can say to you people of the South, both white and black, that the time has passed when you are entitled to assume that the problem of races is peculiarly and particularly your problem,” Harding told the audience. “It is the problem of democracy everywhere, if we mean the things we say about democracy as the ideal political state. Whether you like it or not, our democracy is a lie unless you stand for that equality,” Harding added.

“These things lead one to hope that we shall find an adjustment of relations between the two races in which both can enjoy full citizenship.”

“In anticipation of such a condition the South may well recognize that North and West are likely to continue their drafts upon its colored population, and that if the South wishes to keep its fields producing and its industry still expanding it will have to compete for the services of the colored man. It will realize its need for him and will deal quite fairly with him, the South will be able to keep him in such numbers as your activities make desirable.”

“Is it not possible, then, that in the long era of readjustment upon which we are entering for the Nation to lay aside old prejudices and old antagonisms, and in the broad, clear light of nationalism enter into a constructive policy in dealing with these intricate issues?’

While civil rights activists hailed Harding’s speech many prominent southern politicians denounced it. Mississippi Senator Pat Harrison said, “If the President’s theory is carried to its ultimate conclusion, then that means that the black man can strive to become President of the United States.” Georgia Senator Thomas E. Watson said that the President had sown “fatal germs in the minds of the black race.” And Alabama Senator Thomas Heflin, said, “So far as the South is concerned, we hold to the doctrine that God Almighty has fixed the limits and boundaries between the two races and no Republican living can improve upon His work.”

Less than two years later Harding died unexpectedly at 57, from what is now believed to have been a heart attack. In 1923 he still enjoyed considerable popularity, and some nine million Americans lined the railroads tracks on which his body was returned from San Francisco to Washington, D.C.

Unfortunately for the country and Harding’s reputation, he did not subscribe to the notion of practicing scrupulous personal and administrative behavior. He apparently did not understand that upsetting the status quo often leads to retribution. And it did.

Harding’s unwillingness to immediately fire certain of his self-dealing and mendacious Cabinet members lead to the Teapot Dome and the veteran homes corruptions. All of which came out after his death. Plus, his deplorable marital infidelities also greatly reduced his popular standing – something much more forgivable in certain presidents over the past 60 years.

In retrospect, do the scandals by members of his cabinet, along with his great personal failings to his wife, justify ranking him now as amongst the worst of all American presidents?

Certainly his appointment and support of the aggressive tax reduction policies implemented under Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon (continued under Presidents Coolidge and Hoover) helped lead America into the “roaring 20s” resurgence of our economy.

President Harding also championed the 40-hour work week, tripled the number of improved roads, and created the Office of Management and Budget. As Senator, Harding supported and voted for Women’s suffrage.

And at a critical time in our history, Harding went to Birmingham.

He deserves a far better reputation than he holds today.

Andy Ware

Mount Gilead

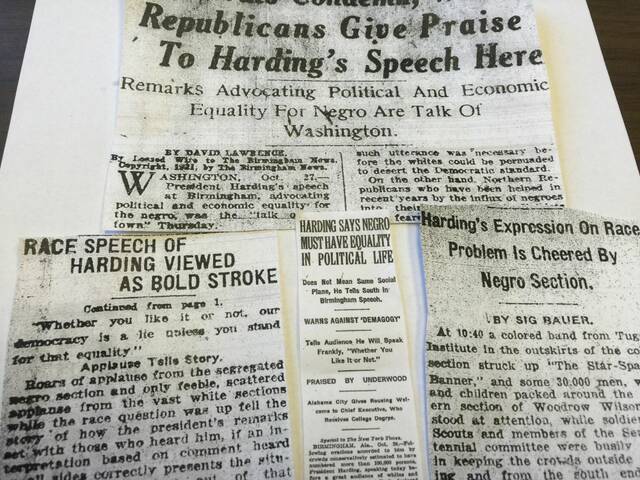

Newspapers document reaction to President Harding’s speech.